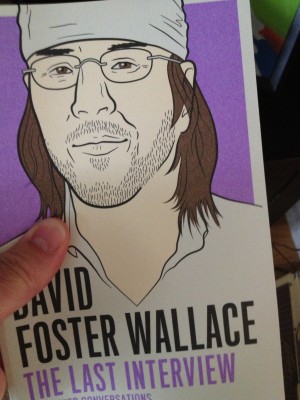

There’s a new issue of the Quarterly Conversation out. Not only does it have my review of David Foster Wallace: The Last Interview, it also contains Andrew Altschul on Wallace’s posthumous collection of nonfiction Both Flesh and Not, David Winters on Sam Lipsyte’s new story collection, and Dev Varma on Azareen van der Vliet Oloomi’s novel Fra Keeler. I included that last one because Varma is a friend and I enjoyed getting to type all of those letters. Enjoy!

Tag Archives: book reviews

Fighting Words

Benjamin Kunkel writes:

Jess Row calls me “dogmatically bigoted” for supposedly characterizing writers from “backward” — his term — countries as formally “backward.” These are fighting words.

This is the very first comment hanging like internet fruit from the ending of Row’s recent essay, “The Novel Is Not Dead,” which appears in the latest Boston Review. I don’t want to explicate, summarize, or disagree with Row’s essay (which I skimmed while eating something crumbly over my keyboard), but I find this mutual raising of backhair interesting and noteworthy.

Because, despite my skimming, my eyebrows did perform a slight uptick of pleasure at the phrase “dogmatically bigoted.” I have always been a fan of the bumptious punch of the adverb-adjective combo. The skimming, by the way, doesn’t really have anything to do with Row’s particular essay. It has more to do with the life/death articles that prey upon various limbs of literature. (There is one even today about the short story at The Millions.) The novel or the story or the epic poem may in fact die, but surely these vampirish little think pieces will live forever. They are the cockroaches of literary culture.

But what’s noteworthy is how I forgot, while reading, that Benjamin Kunkel was an actual person; that is, I forgot that he might not enjoy, much less agree with, Row’s characterization of his literary point of view, that in fact he might even consider Row’s characterization as not just wrong but openly hostile. And yet, despite this, I could see Row’s clear pleasure at deploying a neat phrase, perhaps without a clear vista onto how his punchy eloquence was morphing into fighting words. Maybe he forgot he was actually talking about a real person. Or maybe he knew exactly what he was doing and meant every morpheme.

Either way, it’s an instructive little reminder that Benjamin Kunkel, as well as many other writers we might mischaracterize, is himself emphatically not dead.